Ice Diving Safari: LAKE BAIKAL

Text: Eline Feenstra

Pictures: Rene Lipmann and Olga Kamenskaya

Here, in the heart of Siberia, a rather extraordinary event takes place. Concealed by rising mountains the Earths interior slowly rifts apart, creating world’s deepest reservoir containing roughly 20 percent of the world’s surface fresh water. It is winter now; and the lake is frozen into silence. Only an icy wind sweeps across its surface. But, for us, it is time to go diving!

It’s about a one-hour drive from Siberia’s capital Irkutsk to lake Baikal. The landscape is dissolute and endless, yet surprisingly full of colour. Light yellow soils tint the shimmering snow planes and distant hills are covered with evergreen temperate forest and taiga. It is beautiful, calming.

Gennady Misan sits on the driver seat and rouses himself from the sobriety of the landscape. “Ready, guys!?”, he asks with a warming smile. It is the last hill to climb, in front of us lies also our planet’s most ancient lake: Lake Baikal.

Gennady Misan sits on the driver seat and rouses himself from the sobriety of the landscape. “Ready, guys!?”, he asks with a warming smile. It is the last hill to climb, in front of us lies also our planet’s most ancient lake: Lake Baikal.

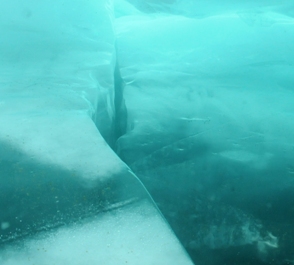

It is like we are hitting something. Everything intensifies: the colours, the air and the Russian music coming from the radio. The sound of rocks crushing the sides of the vehicle on this unpaved road. Gennady speeds up towards the waterfront and before we can even think he throws the Mitsubishi in a spin. This is unbelievable! Frictionless the car turns on it axes. The ice is as strong as steel; baby blue and lined with vertical fractures that form a white labyrinth in this unusual substrate.

A minute later Tatiana Oparina arrives. Tatiana and Gennady are the owners of BaikalTek, the biggest dive operation in the area. She pulls out a camping table to prepare local bread with bacon and mustard. Russian hospitality would not be hospitality without vodka and four little cups are filled to the brim. We sprinkle a few drops on the ice to ask for permission and prosperity. “It is an ancient tradition”, Tatiana tells us. The sweet vodka and sharp mustard immediately open up all my senses. Now, I can feel the icy wind blowing in my face, here in the middle of Siberia.

Diving safari

Lake Baikal is located in the south of Siberia between the Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the Buryat Republic to the southeast. The city of Irkutsk lies close near its southern shores and forms East-Siberia’s biggest economic centre with an extensive industrial sector. The landscape is rendered somewhat grey by a montage of mostly factories and Soviet apartment blocks. The city does, however, get a certain charm from colourful churches and the beauty of the Angara River.

Lake Baikal is located in the south of Siberia between the Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the Buryat Republic to the southeast. The city of Irkutsk lies close near its southern shores and forms East-Siberia’s biggest economic centre with an extensive industrial sector. The landscape is rendered somewhat grey by a montage of mostly factories and Soviet apartment blocks. The city does, however, get a certain charm from colourful churches and the beauty of the Angara River.

Going back in time we leave this urban setting behind for a rural one as part of the ice diving safari we are on. Carried by two massive jeeps we travel from place to place in order to dive in unique environments. At night we stay at primitive settlements made up of traditional houses called isba’s. Isba’s are wooden houses that are still heated by old fashion stoves. A shared banya, which means sauna in Russian, provides extra warmth as well as bathing and forms an important social feature of the community here. During the day we eat on the ice, but at  night we dine together with the locals.

night we dine together with the locals.

Our first dive site is called Olkhon’s Vorota, situated on the southern shore of Olkhon, Baikal’s biggest island. This island is home to the region's indigenous Buryat people once descendants from nomadic tribes in Mongolia. Most of the population in the Irkutsk Oblast nowadays are ethnic Russian who migrated here around the 18th century.

Standing next to the maine, the Russian equivalent for hole in the ice, Tatiana attaches the robe to my BCD. It has been a while since I have been ice diving, but nevertheless I am ready. In fact I could not be more ready for the adventure that awaits me. Descending to a shallow bottom I perform a last equipment check and switch on my light. Unnecessary as natural daylight easily penetrates the crystal clear ice. But something lurks from a much darker depth; reminding us of why we are here.

Cold cuts through the thick neoprene gloves and the air I breathe becomes dense and heavy. In the distance, as the light slowly vanishes, a greenish hue shimmers between the frozen ceiling and the rocky slope. It feels empty, lifeless. But then, as if a window was opened to another world; a field of bright green sponges appears. Hundreds of them. Jumping out of the ground, statically frozen into this inhospitable environment. Adapting to the complete silence of this world, I find myself overwhelmed and mesmerised by a place so alien, yet nature in its wildest form.

Endemic

Lake Baikal counts a current estimate of 1550 animal and 1085 plant species, of which 80 percent are endemic. So is the L. baikalensis unique to the Baikal biotope, thriving due to its oxygenated waters and high dissolved silica content. Their skeletons are made up of silicates, which is rather unusual as most marine creatures consist of calcite or calcium carbonate, the main constitute of limestone. Tiny symbiotic algae are ensconced in the skin of the sponge and deliver energy by means of photosynthesis. It is because of these algae that the sponge has such a striking green colour. Besides this filtering organism, Baikal is home to a stunning number of 260 amphipods. The Acanthogammaridae is quite the extraordinary crustacean. Looking like an armoured weapon with vicious spikes running across its

Lake Baikal counts a current estimate of 1550 animal and 1085 plant species, of which 80 percent are endemic. So is the L. baikalensis unique to the Baikal biotope, thriving due to its oxygenated waters and high dissolved silica content. Their skeletons are made up of silicates, which is rather unusual as most marine creatures consist of calcite or calcium carbonate, the main constitute of limestone. Tiny symbiotic algae are ensconced in the skin of the sponge and deliver energy by means of photosynthesis. It is because of these algae that the sponge has such a striking green colour. Besides this filtering organism, Baikal is home to a stunning number of 260 amphipods. The Acanthogammaridae is quite the extraordinary crustacean. Looking like an armoured weapon with vicious spikes running across its  body, this 10 centimetre long creature is not afraid to come up close and check you out. The main fish is the Omul Salmon, Baikal’s trademark delicacy. But best known to Baikal is the nerpa, the solely mammalian representative and one of only two fresh water seals in the world. Though it is too early this time of year, each spring their pups come out on the ice to catch their first glimpse of sunlight.

body, this 10 centimetre long creature is not afraid to come up close and check you out. The main fish is the Omul Salmon, Baikal’s trademark delicacy. But best known to Baikal is the nerpa, the solely mammalian representative and one of only two fresh water seals in the world. Though it is too early this time of year, each spring their pups come out on the ice to catch their first glimpse of sunlight.

Every winter the lake freezes entirely. Water temperatures reach just below zero degrees Celsius and we encounter weather ranging from minus 25 to plus 5 degrees Celsius. As we exit the maine’s, our suits literally freeze over and this makes it somewhat difficulty to take it of. We use two first stages as a safety measure in case a regulator free flows. A tender on topside monitors us during the entire dive via robes. Tatiana and Gennady enjoy many years of experience and employ comfortable, but most of all safe, practises.

Hummock

Rays of bright sun shatter off the steep cliff that makes up Khoboy Cape, bathing Baikal’s frozen plane with a heavenly silvery white colour. It is our second diving day and it takes a good two-hour drive on the ice to get here. Lines of fractured ice, called hummocks, run across the icy platform reflecting the light, similar to a room full of broken mirrors. Parked near one of the ice pinnacles a white Lada makes this idyllic world somewhat more tangible. The maine has frozen and it takes a good three hours to open it again. Gennady assures us the reward is worth the effort. “Wait until you get down there!”

Rays of bright sun shatter off the steep cliff that makes up Khoboy Cape, bathing Baikal’s frozen plane with a heavenly silvery white colour. It is our second diving day and it takes a good two-hour drive on the ice to get here. Lines of fractured ice, called hummocks, run across the icy platform reflecting the light, similar to a room full of broken mirrors. Parked near one of the ice pinnacles a white Lada makes this idyllic world somewhat more tangible. The maine has frozen and it takes a good three hours to open it again. Gennady assures us the reward is worth the effort. “Wait until you get down there!”

He was right. Because of the full transparency of the ice, you can see the cars and people from below. I absolutely love that. Gennady leads us to one of the hummocks where big boulders of ice are frozen into the ceiling. Their unruly and violent formation reflects nature’s dynamic forces. In between we find little ice caves and niches, some just big enough to squeeze through. The ice feels somewhat rubbery, though rock hard and not slippery at all. Closing in on the island shore the ice forms a roof for tiny creatures that live on the rocky slope. Overthrown by the shadow of the wall, it is darker here; a bit spookier. But so amazing. It makes me feel alive. I am, after all, diving in a hidden world.

Sjamanka

With a depth of 1642 meters Baikal is known as the deepest lake. The lake contains roughly 20 percent of the world’s surface fresh water and its geological history counts back to an estimated 25 billion years. A geological heaven one might say! During the Soviet Union, research was only done by Russian Institutes and very little was translated. Nowadays the area is object of study of an international community and the past 15 years have proven some stunning scientific results. Lake Baikal is a sedimentary basin created by the movement of two tectonic plates that form a rift and strike slip margin, literally moving past and away from each other. The shores of the lake still move apart by several centimetres each year! Due to elevated topography around the lake, the Barguzin Mountains, hundreds of rivers flow into Baikal carrying big loads of sediment. There is only one river draining out of the system. That is the Angara river.

With a depth of 1642 meters Baikal is known as the deepest lake. The lake contains roughly 20 percent of the world’s surface fresh water and its geological history counts back to an estimated 25 billion years. A geological heaven one might say! During the Soviet Union, research was only done by Russian Institutes and very little was translated. Nowadays the area is object of study of an international community and the past 15 years have proven some stunning scientific results. Lake Baikal is a sedimentary basin created by the movement of two tectonic plates that form a rift and strike slip margin, literally moving past and away from each other. The shores of the lake still move apart by several centimetres each year! Due to elevated topography around the lake, the Barguzin Mountains, hundreds of rivers flow into Baikal carrying big loads of sediment. There is only one river draining out of the system. That is the Angara river.

Close to Khuzhir, the main village on the island, the coast dips gently into the water. A huge rock pierces through the ice, playing with the setting sun in the background. The rock, known as Shaman Rock, is one of Asia most sacred places. The story of the God of lake Baikal, named Burkhan, tells the tail of a father and his 330 daughters, a metaphor for all the mountain streams flowing into the lake. When one of his daughters decided to brake free to join her beloved, a ‘warrior river’ in the West, her father threw a large rock to stop her. But his actions were in vain as the Angara river sprouts at the very south of Baikal.

A maine gives us access to the rock under water. It is believed that old Burkhan resides in a hidden cave. Huge ice sculptures form a layered dress around the weathered rock and it is easy to lose sight of each other. But when the visibility decreases and my regulator decides to malfunction, Gennady is right next to me to help me out. I feel safe and comfortable. Upon our ascent I notice a hut placed on the ice, quite close to the maine itself. On top Tatiana shows a conspicuous smile. It is time for banya! The hot steam is welcoming after a cold dive, but when we get too hot, there is really only one way out. Without much thinking I take a giant stride and enter the black water. Crushed by the cold of freezing water and stabbed by what I am pretty sure is a thousand knives, I break the surface again to breath. Within no time I am back on the ice, shaking from my own insanity. But I can only feel empowered by this pure contact with Siberia’s nature.

Spring

An historic locomotive provides shelter from the cold as we change into our drysuits. The 5100-kilometre railroad that connects the lake to Moscow ends here. The picture of what was once a vibrant destination on the Trans Siberia Express, gives now a desolate and nostalgic impression. It is the fifth day into our ice diving adventure and after a long drive from Olkhon we arrive in Listvyanka, a small settlement not far from Irkutsk. Today we conduct an open water dive as the stream of the Angara River prevents the water from freezing.

Thriving on a carpet of stone, the same green sponges form a dense temperate forest. Nothing reminds me of the static appearance we saw on our first dive. Now I can feel the energy and movement. Competing for any space available, these creatures are surely alive. And so are the prehistoric gamaruses, gastropoda, sculpin fish and much more. Moving back to shallower waters the white, almost tropical, sandy bottom get overlaid by a roofless water column and blue sky. Everything breathes. Diving here you feel spring is at the front door.

Pearl of Siberia

Listvyanka is a popular tourist destination due to its local fish market, colourful houses and stunning hiking routes. After building a dam in Irkutsk the water level has risen slightly, which caused minor flooding. An old pier serves as a beautiful dive site, called Krestovka. It wooden logs drifted off, and fill up narrow canyons in the rugged shelf. The pier itself is enclosed between the ice and shore, it parts are covered in a thick bed of green algae. And underneath lies an old rusty cannon, bright red due to iron oxidation. It forms a sharp contrast with the endless blue ice. It is weird, but it almost seems if the colours get deeper after a while. The air sharpens, and roughens us, into a heightened state of observation.

It is not for nothing that people visit this magical place from all over the world. Most will say they find spirituality here. I feel fortunate to see this place as a diver. Entering this hidden underwater world, in such an extreme environment, confronts you with this place in its own kind of way; you are literally in and on top of it. Our ice dive safari has proven to be one of the best dive destinations so far. We have only begun to grasp why lake Baikal is named as the Pearl of Siberia.

INFO BAIKAL

Gennady Misan and Tanja Oparina own BaikalTek. Their dive operation is the largest in the area and provides diving all year round, ranging from ice diving, live-aboards, seal safari’s, technical diving and daily diving. For more information: http://www.baikaldiving.ru

Travel

There is a flight connection from Moscow to Irkutsk. The time difference is 5 to 6 hours depending if you leave from the UK or from the rest of Europe. Getting a Visa does require good organisation and should be obtained at your local Russian embassy.

Accommodation and Food

Because we are on an ice diving safari, we travel a lot and stay at many different places. Housing is primitive, but comfortable. The Russian kitchen is something to experience. On one hand it is mild and solid, but you find also a lot of raw fish, eaten in combination with Vodka!